Sunday 22 January 2017

Byron's Birth and Ancestry

Lord Byron was born on 22 January 1788 in a house on 24 Holles Street in London. However, R C Dallas disputes this in his Recollections and claims that Byron was born in Dover.

He was the son of Captain John "Mad Jack" Byron and his second wife, the former Catherine Gordon (died 1811), a descendant of Cardinal Beaton and heiress of the Gight estate in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Byron's father had previously seduced the married Marchioness of Carmarthen and, after she divorced her husband, he married her. His treatment of her was described as "brutal and vicious," and she died after having given birth to two daughters, only one of whom survived: Byron's half-sister, Augusta. In order to claim his second wife's estate in Scotland, Byron's father took the additional surname "Gordon", becoming "John Byron Gordon," and he was occasionally styled "John Byron Gordon of Gight". Byron himself used this surname for a time and was registered at school in Aberdeen as "George Byron Gordon." At the age of ten, he inherited the English Barony of Byron of Rochdale, becoming "Lord Byron," and eventually dropped the double surname.

He was christened, at St Marylebone Parish Church, "George Gordon Byron" after his maternal grandfather George Gordon of Gight, a descendant of James I of Scotland, who had committed suicide in 1779.

"Mad Jack" Byron married his second wife for the same reason that he married his first: her fortune. Byron's mother had to sell her land and title to pay her new husband's debts, and in the space of two years the large estate, worth some £23,500, had been squandered, leaving the former heiress with an annual income in trust of only £150. In a move to avoid his creditors, Catherine accompanied her profligate husband to France in 1786, but returned to England at the end of 1787 in order to give birth to her son on English soil. He was born on January 22nd, two-hundred and twenty-nine years ago, in lodgings at Holles Street in London.

Catherine moved back to Aberdeenshire in 1790, where Byron spent his childhood. His father soon joined them in their lodgings in Queen Street, but the couple quickly separated. Catherine regularly experienced mood swings and bouts of melancholy, which could be partly explained by her husband's continuing to borrow money from her. As a result, she fell even further into debt to support his demands. It was one of these importunate loans that allowed him to travel to Valenciennes, France, where he died in 1791.

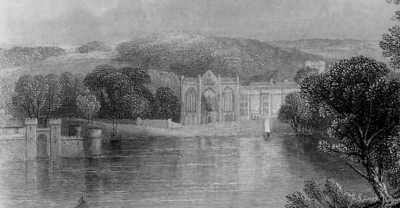

When Byron's great-uncle, the "wicked" Lord Byron, died on 21 May 1798, the ten-year-old boy became the 6th Baron Byron of Rochdale and inherited the ancestral home, Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire. His mother proudly took him to England, but the Abbey was in an embarrassing state of disrepair and, rather than live there, decided to lease it to Lord Grey de Ruthyn, among others, during Byron's adolescence.

Described as "a woman without judgement or self-command," Catherine either spoiled and indulged her son or vexed him with her capricious stubbornness. Her drinking disgusted him, and he often mocked her for being short and corpulent, which made it difficult for her to catch him to discipline him. She once retaliated and, in a fit of temper, referred to him as "a lame brat." However, Byron biographer, Doris Langley-Moore, in her 1974 book, Accounts Rendered, paints a more sympathetic view of Mrs Byron, showing how she was a staunch supporter of her son and sacrificed her own precarious finances to keep him in luxury at Harrow and Cambridge. Langley-Moore questions the Galt claim that she over-indulged in alcohol.

Upon the death of Lord Byron's mother-in-law Judith Noel, the Hon Lady Milbanke, in 1822, her will required that he change his surname to "Noel" in order for him to inherit half of her estate. He obtained a Royal Warrant allowing him to "take and use the surname of Noel only." The Royal Warrant also allowed him to "subscribe the said surname of Noel before all titles of honour," and from that point he signed himself "Noel Byron" (the usual signature of a peer being merely the peerage, in this case simply "Byron"). It is speculated that this was so that his initials would read "N B," mimicking those of his hero, Napoleon Bonaparte. Lady Byron eventually succeeded to the Barony of Wentworth, becoming "Lady Wentworth."

Two Hundred and Twenty-Nine

I have dragg’d to twenty-nine and two-hundred.

What have these years left to mine?

Saturday 21 January 2017

Addendum to a Foreword

Flames leave smouldering words floating upwards as motes caught in the near stillness and silence.

Waiting patiently, sword point downwards, resting in dewy grass. Moist anticipation of the dawn.

Glimpses into the past; glimpses into the future; glimpses amid thickening mist into the present ...

Friday 20 January 2017

Phantoms

Phantoms is not just an homage to one person, but for all who have a special attachment to a bygone time:

In part, we are,

In part, we always were

Phantoms from another time.

Time travellers. Ghosts.

Fading in. Now fading out.

Like spectral curls of mist

From time past to time present.

And back to whence we came.

She materialised on that golden sunshine day three decades ago. Until that moment she was a canvas not yet painted; a sculpture not quite formed; though within my being she existed as surely as did I. That story lives on and will remain alive whilst breath is drawn. But there is another yet more distant past to visit. Byron's ...!

Tuesday 17 January 2017

Adieu Remembered England

It was painful to witness the deterioration of England. This was magnified by the eradication of my old London haunts. Surroundings succumbed to a decline probably in evidence since the nineteenth century, which accelerated throughout the twentieth century; not helped by two devastating wars.

My father was also deteriorating, having a heart condition for which medication had been prescribed. Yet he was fiercely independent and would not allow any interference. Knowing it would be fatal to stop taking his prescribed tablets, he nevertheless did stop taking them ― no longer able to live in a world without his first, last and only love whom in life he was unable to show the appreciation she perhaps deserved. Yet who are we to judge? Words that were her last eight years earlier nevertheless linger in the mind to burn away the veneer of romantic illusion that can grow like moss on memory.

In the weeks following my father’s death something happened that would provide a unique portal through which I almost glimpsed things as they had been in my youth. Following the discovery of my father’s body in the house where my parents had spent so much of their lives ― a house, moreover, now more resembling Mrs Havisham’s in Charles Dickens’ Great Expections ― an altered state of consciousness occurred which, coupled with the inevitable adrenaline surge that accompanies stress in crisis, found me walking the streets aimlessly, and calling on people I had not seen for decades.

Byron’s forbidden love with Augusta Leigh exacted from her a curl of chestnut hair with glints of gold, and the following lines tied with white silk:

Partager tous vos sentimens

Ne voir que par vos yeux

N’agir que par vos conseils, ne

Vivre que pour vous, voilà mes

voeux, mes projets, & le seul

destin qui peut me rendre

heureuse.

On the outside of the small folded packet Byron penned these words, followed by a cross:

"La Chevelure of the one whom I most loved +"

The equidistant cross now became their emblem. Curiously and coincidentally, I sign my own name with an equidistant cross preceding it; though for reasons entirely other than the mathematical symbol for the joining of two parts to signify sexual consummation. Byron made a note in his journal to have a seal made for him and Augusta with their “device.” This happened at the end of November 1813.

Partager tous vos sentimens

Ne voir que par vos yeux

N’agir que par vos conseils, ne

Vivre que pour vous, voilà mes

voeux, mes projets, & le seul

destin qui peut me rendre

heureuse.

On the outside of the small folded packet Byron penned these words, followed by a cross:

"La Chevelure of the one whom I most loved +"

* * *

It once was but is no more,

You said of our beloved city

That day we spoke from afar.

I said: 'Tis a pity! 'Tis a pity!

And true; so very true.

I shall never return.

So alien and blue,

And now I learn

It resonates with neither

Me nor you.

Why did time efface and wither

London of the few

Who made it swing-a-long

To an upbeat song

As cameras clicked

And hearts ticked

So merrily; so merrily?

Fare thee well, Chelsea!

Adieu, Holloway, Highgate

Hill and Hampstead Heath!

Goodbye London Town!

Then we put the 'phone down,

And never again

Spoke about its end.

You said of our beloved city

That day we spoke from afar.

I said: 'Tis a pity! 'Tis a pity!

And true; so very true.

I shall never return.

So alien and blue,

And now I learn

It resonates with neither

Me nor you.

Why did time efface and wither

London of the few

Who made it swing-a-long

To an upbeat song

As cameras clicked

And hearts ticked

So merrily; so merrily?

Fare thee well, Chelsea!

Adieu, Holloway, Highgate

Hill and Hampstead Heath!

Goodbye London Town!

Then we put the 'phone down,

And never again

Spoke about its end.

"I like London," she said

On that day we met

All those years later.

'Twas my birthday

And I thought there

Was a time when I

Loved London too,

Much more than you

Or anyone I knew

Could construe.

But that London

Is long gone —

That London is now

A ghost of yesterday.

"I like London," she said.

My response was swift,

And fixed in its view —

"London, my dear friend,

Is dead."

Byronic Legacy

Newstead Abbey Park family house in many acres of private woodland.

My mother wrote a modest memoir, pencilled in her beautiful copperplate hand, titled Recollections. She commented that Newstead “held a secret,” adding that “the walk to the Abbey was short. It was in the same grounds as my parents’ home. I remember how absorbed Seán became with the whole atmosphere of the place — very intent.”

I knew little concerning Byron’s life when I was a child, and would not trouble to read a biography about him until I was nineteen. Yet I recall the poet’s name cropping up in hushed tones when I was still quite young. It did not take long for an awareness to develop of the family connection, albeit one that was to remain firmly in the cupboard where Byron’s skeleton nevertheless rattled from time to time, despite the bloodline’s illegitimate origin. Unlike today, such things were not considered at all appropriate for dissemination. Hence much caution was in evidence about the Byronic legacy my mother and I had inherited. In those days it would remain a topic unmentioned in company, and even in private it was to be a mysterious family legend.

By the time I had my first complete work published (as opposed to contributions I had made to anthologies edited by other authors) there was no question in my mind that the book would be dedicated to the memory of my illustrious ancestor Lord Byron.

Not unlike the poet’s early work Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, my first complete work in print became an immediate bestseller. My mother recounted in her Recollections:

“Newstead held a magic for me. Seán loved it too. He went about the grounds with my brother, Colin, who had a tree house and a gun. Dad only allowed Colin to have a gun because the poor rabbits were dying in agony from myxomatoses. I was given a book of English poetry by my father. Seán picked it up and out of the one thousand one hundred and fifty poems chose Byron’s She walks in Beauty to read. I don’t think Seán even knew the connection between Lord Byron at that time.”

The longest absence from Newstead as a child was the period spent in Canada where my parents sought their future and fortune overseas. “I heard some lovely reports about Montreal, which I related to Allen,” my mother recorded.

“These little stories fired our imagination and we decided to go. Seán was aged three. Allen went first by air. Seán and I stayed at home until three months later when we were passengers on the Aquitania from Southampton to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Allen had been in Toronto for three months, but we settled in Montreal, a beautiful city built around a mountain topped by a cross. This seemed significant to me at the time. I had collected crosses for years. The highlight of our day was to take the bus to St Catherine’s Street where we would have a chocolate éclair each with a beverage. Weekends would find the three of us walking up the mountain or visiting the lake. It was all very pleasant, but our future in Canada was really doomed from the start as many things were not what we had been used to in England. The accommodation left much to be desired, and Allen discovered that work was in short supply. So back home we came on the Ascania, a much smaller version of the Aquitania, which proved to be a smelly little ship. We docked at Liverpool and from there we sailed to Dublin where we stayed with Mr and Mrs Berry. He was the keeper of DublinCastle.”

The rickety and foul-smelling tug called the Ascania should have been scrapped years before we boarded it, and almost certainly was soon after our arrival in Liverpool. This was in marked contrast to our time at Dublin Castle as a guest of the Berrys. In the previous century the spectre of a frail gazelle of a girl of medium height, in Regency clothes, flitted down the corridors with large, enquiring eyes brimming with tears. She occupied the shadowy places I now found myself wandering. I would write her biography one day, and it was published in the saddest year of my life. My biography of Lady Caroline Lamb was the last book my mother would read before she died.

Within a couple of months my parents had left Ireland, and once again I was amongst the familiar scenery of our beloved Newstead Abbey Park. Soon after my fifth birthday, however, I began attending Hungerford School in north London, and visits during holidays were all that now seemed possible. My mother’s Recollections continued:

“A lovely city, Dublin, but it held no future for us, so we came back to England via Dunleary to Holyhead, staying in Nottinghamshire. Allen went ahead of me to London. Seán and I joined him shortly after to find temporary accommodation in Highbury Hill. Then we found rooms in Holloway, followed by the Mansions where we had a porter and cleaner. I recall how eager Seán was to read and write, and he made fast progress. Seán had talked at a very early age. It was when he went to school that we noticed the early signs of his originality. He was different, always different from others, and he had a way with words from the start. He was also very perceptive right from his first year. He seemed to read one’s thoughts and feelings.”

Visits to Newstead nevertheless continued on a fairly regular basis. It was in the Abbey’s vast collection where I discovered a pencil portrait of my Dublin Castle phantom: a quarter-length drawing of a pensive young girl with slightly downcast eyes. Mesmerised by the elfin creature, a window seemed to open within my subconscious mind to rich colours lit by candelabras stuffed with melting candles, heavy brocades and tapestries, exquisitely decorated harpsichords, sombre paintings in large frames, dark oak furniture, and reverberating, melodic strains from another time. Amidst all this appeared a ghostly female with rosebud lips, fawn curls and large, sad eyes.

Momentary glimpses of Romanticism’s haunted realm where the flickering, wavering image glided in step to echoes from a tinkling, distant spinet, offered somewhere I would visit throughout my life thereafter — a primitive form of time travel. The identity of my apparition became soon became apparent. It was Lady Caroline Lamb.

Caroline’s husband was Secretary of Ireland in 1827, two years after their separation, and he would have stayed at Dublin Castle for long periods of time. This was three years after the tragic death of Caroline’s fatal passion Lord Byron. She had stayed at the castle prior to when her husband, William, became Secretary. He almost certainly accepted the post because he could not bear to watch her suffering any longer in the wake of the terrible news about her lover Byron. It would destroy her in the end.

My psychic portal grew faint as childhood innocence itself gradually eroded over the years, but later in life I renewed my acquaintance in becoming the biographer of Lady Caroline Lamb. Lord Brocket invited me to Caroline’s country residence in Hertfordshire, Brocket Hall, and Lady Brocket entered into a correspondence where she told of the haunting at the Hall. In February 1992, Lady Brocket wrote of “a woman in the Ballroom” when she was playing some Chopin on the piano.

Frédéric Chopin ― my mother’s favourite composer ― and mine. How memories are stirred whenever the sound of his music fills the air. Each visit I made to Chopin’s tomb at Père-Lachaise in Paris, I would invariably discover freshly cut red roses on the grave ― lovingly placed by a mysterious admirer.

My mother playing some Chopin on the piano at our Newstead home.

When we arrived in London from Ireland, having settled in a first floor flat in Islington, my father ordered a rosewood piano to be delivered. It remained with my parents to the end. On this instrument my mother would continue to play the music of Chopin in those early days. When we removed to the Mansions, where Fred the porter and Alice the cleaner were part of the fixtures and fittings, the piano followed. Its final destination was the house my parents purchased within a short walking distance.

When we arrived in London from Ireland, having settled in a first floor flat in Islington, my father ordered a rosewood piano to be delivered. It remained with my parents to the end. On this instrument my mother would continue to play the music of Chopin in those early days. When we removed to the Mansions, where Fred the porter and Alice the cleaner were part of the fixtures and fittings, the piano followed. Its final destination was the house my parents purchased within a short walking distance.

The children at Hungerford School adored my mother. They called her “flower face” because of the curls around her constantly smiling face. She was at her most beautiful during this period and attracted many admiring glances — yet she remained ever childlike and innocent, charming everyone along the way, to the end of her life.

Despite the transparent naîvety that never left her, my mother led the way and made things happen. She wanted a child. My father was less convinced. When we returned to England from overseas, my mother would be the one to discover and organise each of our homes. It became apparent to me in later life that she earnestly wanted me to find the romantic fulfilment that she felt she had been denied all along.

Some years I won a national poetry competition with To Nature ― On Autumn:

’Twas down a little country lane

Leaf-strewn, in coloured hue,

That to my memory will remain

The joy I found in you.

Sweet whisperings from a brook nearby,

Sad notes of birds’ late song,

Filled my heart with an ecstasy.

Dear Peace, for you I long.

When back amid the noise and pain

Of daily toil and strife,

Locked in my heart that country lane,

Brings reality to life.

Notwithstanding the influence my mother had on these three verses, Newstead Abbey Park had provided for me the brook and nearby country lane. My mother had much older memories. When she was very young and her parents had moved from Derbyshire to an idyllic setting at Wollaton, a brook ran along the bottom of the country lane where their house was situated. She often spoke about her first home. Newstead, in many ways, would magnify its joys and aspects ― adding acres of woodland and more besides. After the Newstead property and its acreage were sold in the early 1960s, my grandparents lived out their remaining days in a house built for them on land purchased at Wollatan Park. The haunting of their home by a cold presence that apparently manifested as a spectre, allegedly causing my grandmother to fall down the rockery one evening, precipitated this final move. She lay undiscovered for some hours before her husband returned. Presentiments of doom and disaster seemed to intrude her everyday existence thereafter and she never properly recovered.

Newstead was to become for me a symbol of all that belonged to the old world that was already irrevocably, moment by moment, slipping away. More than anything my mother wanted me to find real happiness; something that was always just out of reach for her. This is reflected in the lines I would write in a novel published some eight years after her death.

“The world we once inhabited has gone. … This is your time and your world. Find happiness in it, if you can.” So tells Mina Harker to her son, Quincey, in Carmel, my sequel to Bram Stoker’s gothic masterpiece Dracula. Yet it could have been my own mother speaking. Her world was fast disappearing as two catastrophic wars heralded the quick demise of a cultural identity and spiritual destiny that had lasted two millennia.

Blood Descent

Lord Byron (1801). The Author (1947).

Thank heaven for that place in Newstead Abbey Park, which stood in the shadow an old monastery, and now still older mansion, of a rich and rare mixed Gothic. Here I would spend time encapsulated in a world that remained somehow in its own history, set in the midst of forest trees, which very semblance stood petrified in yestercentury — not swaying, nor even fluttering in the night winds of war.

Yet here, too, I would become acquainted with the mysterious effect of the supernatural, which would, many years later, oblige my grandparents to quit their forest home following an unearthly spectral haunting. A malevolent ghost-like figure was believed to be responsible for my maternal grandmother’s early death.

My mother was a sweet and innocent soul who sought beauty and goodness where it seldom seemed to dwell. She sang, wrote poetry, and played the piano a little (especially her favourite composer, Chopin) when she was young, but the ultimate prize of happiness, as envisaged in her heart, seemed to elude her. So she stopped doing these, as life itself grew tiresome as the inevitability of compromise dawned. Yet a sparkle in her blue eyes remained from a time when dreams had not flown.

Dorothy, my mother, was born at a time when the previous world conflict had practically wiped out an entire generation, and was growing tired by the spring of 1918. Her paternal grandparents, both quiet by nature, had a farm in Derbyshire. The abode of her maternal grandparents, also located in Derbyshire, was the destination for Christmas holidays. These would be spent with her parents who themselves resided in close proximity to Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire’s Sherwood Forest.

A semi-ruined priory: home to the Byron family for three centuries.

Once the habitat of the celebrated poet and his ancestors, Newstead would become a symbol of all that is Gothic and Romantic, which now, irrevocably, has slipped into the reservoir of fragmented memory. This is where I “played as a child in the avenues of sombre forest trees in Lord Byron’s gloomy abode where the fading twilight coupled with the moan in leafy woods to herald the filmy disc of the moon.”

I was conceived in October 1943, as the war in Europe prepared to reach its climax. Thus, nine months later, came into the world “the great, great, great grandson of the famous poet, through an illicit liaison between his lordship and a maid at Newstead Abbey.” Many years later, I would thank leading Byron scholar Professor Leslie A Marchand “for his help and comments in private correspondence about the ‘records of births and deaths of the lower (servant) class in those days’ when trying to establish facts about the poet and Lucy, my great, great, great grandmother.”

Portrait of Lord Byron (oil on canvas) by the author.

Owning this blood connection would lead to certain expectations, as reflected in the following from a gothic magazine: “He was invited to appear on Central Television’s Saturday Night Live, but only on condition that he ‘dressed like Lord Byron’.”

Author (including shield from his personal coat-of-arms).

Byron was seldom without consolation of the female kind and of the various servant maids who slipped between his sheets to keep him company at Newstead, Lucy was far and away his favourite. He called her Lucinda, but in the following lines she appears as Lucietta:

Lucietta my dear,

That fairest of faces!

Is made up of kisses …

A letter, 17 January 1809, to John Hanson confirms that “the youngest is pregnant (I need not tell you by whom) and I cannot have the girl on the parish.” On 4 February 1809, Byron wrote to Hanson:

“Lucy’s annuity may be reduced to fifty pounds, and the other fifty go to the Bastard.” He had originally provided her with an annuity of one hundred pounds. Three years after making Lucy pregnant he put her in charge as revealed in a letter to Francis Hodgson, written from Newstead on 25 September 1811: “Lucy is extracted from Warwickshire [where his and her son had been weaned]; some very bad faces have been warned off the premises, and more promising substituted in their stead … Lucinda to be commander of all the makers and unmakers of beds in the household.”

Byron’s letters might suggest a callousness in his relationships that is perhaps unwarranted, but when his illegitimate child by Lucy was born, he wrote a poem in which he hailed his “dearest child of love.” He had always wanted a son and Lucy provided him with his first and last. Surviving progeny that followed were all female. He composed To My Son when Lucy’s child was born:

Those flaxen locks, those eyes of blue,

Bright as thy mother’s in their hue;

Those rosy lips, whose dimples play

And smile to steal the heart away,

Recall a scene of former joy,

And touch thy father’s heart, my Boy!

And thou canst lisp a father’s name —

Ah, William, were thine own the same, —

No self-reproach — but, let me cease —

My care for thee shall purchase peace;

Thy mother’s shade shall smile in joy,

And pardon all the past, my Boy!

Her lowly grave the turf has prest,

And thou hast known a stranger’s breast;

Derision sneers upon thy birth,

And yields thee scarce a name on earth;

Yet shall not these one hope destroy, —

A Father’s heart is thine, my Boy!

Why, let the world unfeeling frown,

Must I fond Nature’s claim disown?

Ah, no — though moralists reprove,

I hail thee, dearest child of love,

Fair cherub, pledge of youth and joy —

A Father guards they birth, my Boy!

Oh, ’twill be sweet in thee to trace,

Ere age has wrinkled o’er my face,

Ere half my glass of life is run,

At once a brother and a son;

And all my wane of years employ

In justice done to thee, my Boy!

Although so young thy heedless sire,

Youth will not damp parental fire;

And, wert thou still less dear to me,

While Helen’s form revives in thee,

The breast which beat to former joy,

Will ne’er desert its pledge, my Boy!

The Byron family coat-of-arms.

To My Son, incorrectly dated 1807 by Thomas Moore, was first published six years after Byron’s death. Lucy’s pregnancy, of course, did not take place until early 1809. Moore misread the date. Furthermore, the housemaid did not die the early death of the young mother eulogised by the poet whose “lowly grave the turf has prest.” According to the housekeeper, Nanny Smith, Lucy overcame the “high and mighty airs she gave herself as Byron’s favourite,” married a local lad, and ran a public house in Warwick. The fate of the child enters the forlorn and forgotten realm of so many illegitimate offspring of servants, and does not resurface again until a century later when my Derbyshire maternal grandparents returned the bloodline to Newstead Abbey Park where they purchased twenty or so acres and had a comfortable lodge built almost within the shadow of Byron’s ancestral home. In the poem, Byron changed the scenario of Lucy’s end to conform to the sentimental moralising of the period, which required that the fallen woman must pay with her life: “The mother’s shade shall smile in joy, / And pardon all the past, my Boy!”

The poem addresses Byron’s natural child, challenging the convention that would withhold from his “little illegitmate” a father’s loving concern, along with any claim to social position. Byron’s pride, along with his sense of honour, was offended by the common practice of turning out pregnant maidservants. He knew the fate of country girls who bore illegitimate children, surviving on the pittance provided by parish poor rates, the workhouse, or making their way to the nearest city and entering a life of prostitution. Along with keeping Lucy employed, Byron made provision — exceptionally generous by the standards of the day — for her and their child in his will. Lucy was to have an annuity of £100 (later reduced to £50); the other £50 was to go to the child.

The poet’s only legitimate child was born of Annabella, Lady Byron, on the night of 9 December 1815. She was named Augusta Ada. His half-sister, also called Augusta, would later tell him that while Ada resembled her mother more than Byron, “still there is a look. I never saw a more healthy little thing. It was a melancholy pleasure to see Lady B for I had suffered great uneasiness of which I had given you hints.” Well might she feel uneasy, for, on 15 April 1814, she had given birth to a daughter of her own, Elizabeth Medora, whose father was rumoured to be Byron. There was absolutely no way he could be sure that he was the father, even though at the time this was assumed to be the case, and he never acknowledged the fact. He nonetheless showed great fondness for Medora, and Lady Byron herself was struck by the child’s extraordinary beauty. Absence of proof positive allowed licence for speculation, needless to say, of which the most astonishing example was the theory advanced by Richard Edgcumbe in Byron: the Last Phase (1909) that Medora was Byron’s daughter by his boyhood’s love, Mary Chaworth, obligingly adopted by Augusta. However, his half-sister Augusta did write to him of “a likeness in your picture of Mignonne [Medora].”

Claire Clairmont gave birth at Bath to a daughter, on 12 January 1817, whom she named Alba, after Albé, the name the Shelley family had assigned to Byron while in Geneva. Byron asked rhetorically: “Is the brat mine? — I have reason to think so.” Before leaving England with her mother, the child was baptised “Clara Allegra Byron, born of Rt Hon George Gordon Lord Byron ye reputed father by Clara Mary Jane Clairmont.” Allegra was spoilt, wilful, and undisciplined — a carbon copy of her father when he was a child. By the age of four Byron arranged for her to be enrolled at a Capucine convent at Bagnacavallo, Italy. On 20 April 1822, Allegra, aged five years and three months, was dead, to the profound grief of the nuns who regarded her a very special child. When Byron heard the news he sank into a chair, and asked to be left alone. Three years later he told Lady Blessington:

“While she lived, her existence never seemed necessary to my happiness; but no sooner did I lose her than it appeared to me as if I could not live without her.” The body of Allegra was sent back to England to be buried at Harrow Church near Peachey Stone where the poet had spent so many hours as a boy. The rector of Harrow refused to erect Byron’s proposed tablet, and the child was buried just inside the threshold of the church. Byron had wanted the words: “I shall go to her, but she shall not return to me.”

The author's portrait hangs alongside that of Lord Byron in a room full of family heirlooms.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)